Vol. 2, Issue 33 - Interview with Carol Monahan (Wizards of the Coast)

Johto Times interviews Carol Monahan, the former Director of Sales & Logistics at Wizards of the Coast, between 1993–2000. Plus, a recap of the latest Pokémon news

Welcome to Vol. 2, issue 33 of the Johto Times newsletter! Every so often, Johto Times is fortunate enough to speak to people that played an important part in Pokémon’s history and highlight their stories and contributions. I am grateful to be doing that again today with Carol Monahan, the former Director of Sales and Logistics at Wizards of the Coast, who worked for the company between 1993 and 2000. When the company received the licence to the Pokémon Trading Card Game, Carol was responsible for getting large volumes of product shipped out to retailers. It's an insightful interview, showing the earliest days of the Pokémon TCG from an angle you may not have heard before, and we hope you’ll enjoy it.

Then, as usual, we’ve also got a recap of the latest Pokémon news!

News

We are saddened to report that Rachael Lillis, the actress who provided the voices of Misty, Jessie, Jigglypuff, and many other characters in the English adaptation of the Pokémon anime, has passed away. She died on August 10th, 2024, after a battle with cancer. She was 55 years old. We are devastated by this news, but grateful for her massive contribution to the Pokémon anime, where her memory will continue to live on.

We have postponed next week's planned issue and will be putting together a special tribute issue in memory of Rachael instead. We welcome our readers to contribute some words for it, if they feel comfortable doing so, by sending their messages of tribute via email to us by Sunday, August 18th, 2024, at 18:00 UTC. In order to include as many reader tributes as possible, we request that you please limit this to a short paragraph, around 100 words. We will attempt to publish as many as we can in next week’s issue, but apologise if we can’t include everyone.

Source: Variety

The 2024 Pokémon World Championships will be held from tomorrow, August 16th, 2024, until August 18th. The annual tournament returns once more, where the best Pokémon players from around the world compete in titles such as Pokémon Scarlet & Violet, Pokémon Unite, Pokémon GO, and the Pokémon TCG. For those who use Twitch, The Pokémon Company have revealed some Twitch Drops for the event, allowing you to claim in-game bonuses for watching the World Championship live streams. Our friends at Pocket Monsters have shared a list of all the bonuses and how you can obtain them. Be sure to check it out!

Source: Pokémon, Pocket Monsters

The Pokémon GO Community Day Classic for August has been revealed. You can catch Beldum on August 18th, 2024, between 14:00 and 17:00 local time. Full details on the event, including the bonuses and events that will be taking place at the time, can be found in the source link below.

Additionally, Niantic have confirmed the next three Community Day events for the next season: September 14th, October 5th, and November 10th, 2024. At the time of writing, we do not know which Pokémon will be the focus of these events.

Source: Pokémon GO

Suicune is coming to Pokémon Sleep in early September, completing the Legendary Trio, after the Entei and Raikou events which took place earlier this year. More details on this event will be revealed soon.

Source: Pokémon Sleep

Feature: Interview with Carol Monahan (Former Director of Sales & Logistics, Wizards of the Coast)

Carol Monahan was the Director of Sales & Logistics at Wizards of the Coast (WotC), and worked for the company between 1993 and 2000. During the last few years of her tenure, the company obtained the licence to print and distribute the Pokémon TCG, and Carol played an important role ensuring the products were shipped out to retailers. I’m thrilled to share our interview with her!

It’s wonderful to speak with you, Carol! Could you please introduce yourself to our readers here at Johto Times?

Carol:

My name is Carol Monahan, and I live in Seattle with my husband (award-winning game designer) James Ernest, our 22-year-old daughter Nora, and our two guinea pigs, Pinky and Lucinda. I live in a house “paid for by Pikachu”.

You worked with Wizards of the Coast for seven years between 1993 and 2000. How did you get your start with the company?

Carol:

Back in 1989, James and I moved to Seattle because it seemed like it would be more exciting than staying in St. Louis, where he was working on a degree in engineering and I had a dead-end job at an extended warranty company. When we hit Seattle, James pursued a juggling career, and I worked temp jobs, which allowed me to hare off with him to work on cruise ships or go to festival gigs.

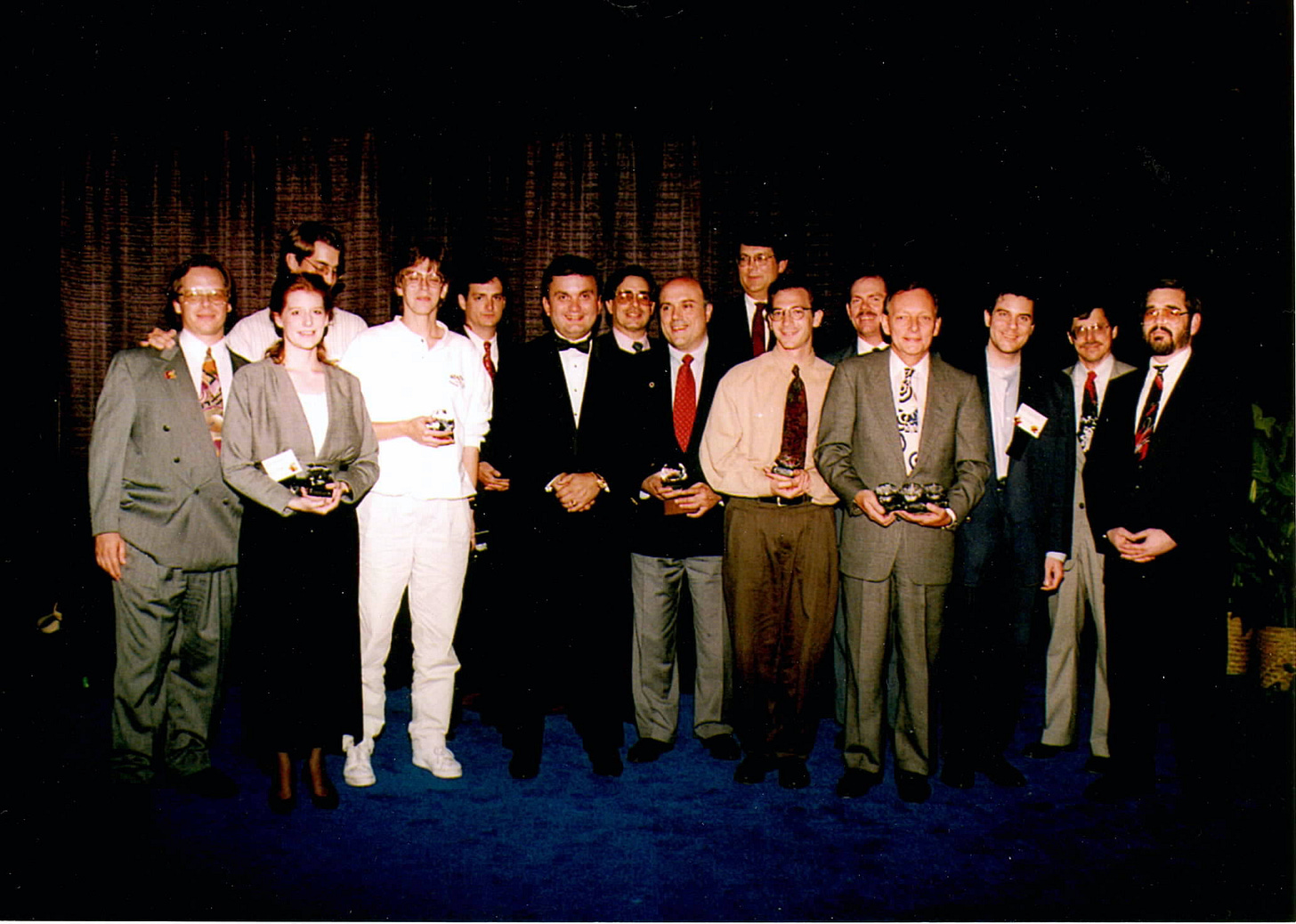

Through my temp jobs, I became friends with Kathy Ice (Editor), who introduced me to Dave Howell (Author and Game Designer). He was already working with Wizards, at that time a tiny kitchen-table company with only one product – a roleplaying supplement, The Primal Order. Soon after, I met Peter Adkison (former CEO of Wizards of the Coast) at a sci-fi convention where I had a guest pass for being an artist’s model. James and I, along with many of our friends, gradually got more involved with Wizards in the run-up to Magic: The Gathering. In 1993, as Peter went looking for funding for the first print-run, he hit up everyone he knew. I was so sure the product would be a success that I maxed out a $1000 credit card in order to invest. Through the fall of 1993, I was part of a group of shareholders and friends of the company who participated in regular company meetings in Peter’s house.

Magic took off insanely quickly, and the chaos soon became obvious. After staying up most of one night to help Dave Howell finish typesetting the Arabian Nights set, I started insisting that they needed to hire me, just as soon as they started having regular payroll – at that point, they were all working without pay. By November, they did start payroll, with everyone getting $9/hour, and the first open job that came up was Sales. They were considering someone experienced from the industry, who they would have to relocate from the Midwest. Since I was used to being a temp, I offered to let them try me out temporarily – I felt sure I could make a contribution, and I wouldn’t require relocation expenses! After just one week, they officially made me a regular employee and gave me the title Director of Sales. I got to share a desk, phone and Mac Classic II computer in Peter’s basement rec room with two other employees.

How would you describe the working environment at WotC during your time there?

Carol:

Wizards grew incredibly quickly, changing drastically and frequently. After my first two months on the job, the company moved out of Peter’s house and into half of a one-story office building. The move happened while I was on my first business trip, to Europe, with Peter’s then-wife Cathleen, and I came back to find I had an entire office to myself, with a window, furnished with a grey metal executive desk from Boeing surplus. And my own boombox!

For the next year or two, we were hiring people as fast as we could find them, and most of the folks who were willing to take a chance on a crazy startup with a “fad” product were friends of friends of people already working there, so we assembled a lot of gamers and goths in the early days. My husband even did a stint with the company doing technical writing.

Peter started work on an MBA, and we all got to experience that second-hand, as he brought whatever he was learning back and tried it out on us. We reorganized about every six months, and the org charts got descriptive nicknames – I particularly remember “the spiderweb”, which had all of the divisions spreading out with the leadership team at the center.

We had a traumatic reset at the end of 1995, with a big round of layoffs right before Christmas, just as we were moving into a larger office park. All of us managers were initially told we needed to cut back, but I pointed out that Sales was the department responsible for bringing the money in, while everyone else was spending it, and perhaps it wasn’t really necessary to fire any of our multi-million dollar customers’ account managers, or any of the folks who were making sure that products were shipped, or any of the folks making sure those shipments were documented correctly so accounting could send out invoices. I’m happy to say I won that one.

It was a classic startup situation, with everyone scrambling to keep up with a stream of new developments: launching a web presence (when the web was a brand new thing!), creating a tournament system, opening a chain of retail stores, expanding overseas, purchasing TSR (the original role-playing company, publishers of Dungeons & Dragons). The pace was relentless.

We kept our spirits up [by] collecting vast arrays of desk toys and waging Nerf battles. On one memorable occasion, I was on the phone to a customer when a whole squad of guys dashed into my office with Nerf guns and a Super Soaker. I had to apologize profusely to the customer, after I stopped screaming.

In 1998, WotC acquired the publishing rights to the Pokémon Trading Card Game, which were held until reverting to Nintendo in 2003. What’s the story behind WotC obtaining the licence?

Carol:

Ah, there’s a lot of story there, and I only know some of it. We had a VP of New Business Development & Licensing, Rich Fukutaki, a toy industry veteran, who got the deal done, and my recollection is that it was set up prior to (or very close to) the US release of the Pokémon video game. Wizards had a US Patent on trading-card games, which had been variously licensed by other companies or ignored/challenged. I believe the folks in Japan saw partnering with Wizards as a way to get their TCG into the US market without having to navigate the patent, as well as to have the game receive the benefit of all of the infrastructure that was already in place for Magic.

The Pokémon TCG was already an established product in Japan, printed by Media Factory from 1996. WotC were tasked with adapting the game for an English-speaking audience. In your experience, what was the company’s mood toward Pokémon?

Carol:

Initial reactions inside Wizards were often, “So, it’s for little kids?”, “So, it’s just for the mass-market stores?”, etc. and the R&D group weren’t thrilled that they were being brought an already-baked game – they would have preferred the freedom and glory of designing a new game from the ground up. And at first, no one had any idea of how big it would be.

Some of the skepticism came from the fact that we’d seen generally disappointing results from licenses to that point. Games based on BattleTech, Hercules, and Xena hadn’t exactly set the world on fire.

As the Pokémon video game’s popularity grew, Wizards saw that the demand for the TCG would be solid – but we still didn’t realize the scope of what we were about to deal with. Magic was bringing in ~$200 million a year to Wizards by then (up from about $25 million in 1994, its first full year), and Wizards was the biggest TCG publisher [in the world].

Editor's Note: According to additional information from Carol Monahan, this statistic is an estimate "based on sales ranking that was reported in industry press. There were other companies with TCGs that were going concerns by 1998, such as the Decipher with their Star Trek TCG, but Magic was consistently out front on the sales charts until Pokemon came along”.

One dynamic that I’ve seen multiple times over the years is that the mass market is incredibly risk-averse, while the hobby market is populated with folks who have some understanding of collectibles. This makes forecasting the demand for a product like a TCG incredibly hard. A Target or Wal-Mart will only order tiny amounts of an untried product, but the moment it’s a hit, they’ll storm in demanding vast quantities. Hobby works in reverse: they’ll try to capture the surge of sales when a hot collectible is brand-new, sometimes even overestimating what they need, and then retreat as it becomes more widely available. In the case of quality products with longevity, this will eventually reach an equilibrium, where more product is going through mass-market/non-specialist channels.

We definitely saw this with Pokémon. Here we had this “mass market” product, but we were getting anemic initial orders from the stores it was “destined” for, while the hobby distributors were ready to buy. Wizards doubled down on marketing to the broad market, concentrating on a mall tour that was coordinated to some extent with Nintendo Pokémon promotions. I vaguely recall that there were some events where the card part was absolutely mobbed, rather to the detriment of the video game promotion.

Inside Wizards, we were scrambling, but jubilant, as the big mass-market chains woke up and the orders surged, while orders for the hobby market remained exceedingly strong.

I think it would be interesting for our readers to get an insight into the process behind printing and distributing the Pokémon TCG. What kinds of logistical challenges did WotC face when dealing with large volumes of product, and how were you able to overcome them?

Carol:

When Wizards set out to make Magic: The Gathering, there were no printers who were completely prepared for the challenge of making randomized playing cards. The printers who made standard card games and poker decks were able to print on high-grade cardstock and do varnishing and corner-rounding, but only made pre-set decks and packs. Trading-card printers were set up to make random packs, but weren’t set up to print playing cards or package decks of cards into boxes.

Carta Mundi stepped up for Magic, by cleverly repurposing some of their existing equipment, and – as Magic’s success grew – they invested heavily in expanding their operations. By the time Pokémon came out, there were several card-printers who had jumped into full TCG production, but there were still constraints of capacity, both in terms of getting press and assembly time, and [in terms of] securing enough appropriate cardstock.

Wizards, after initially using third party logistics partners, had set up their own warehousing operations in Grand Prairie, TX, and I was involved in the growing pains of selecting and implementing an IT solution there. We had acquired TSR by then, so we had hundreds upon hundreds of SKUs (Stock Keeping Unit), ranging in size from individual booster packs to large boxed games. This led to situations of pallet locations being assigned to hold more boxed games than could possibly fit, or finding other pallet locations containing only a sad little stack of a dozen paperbacks. We eventually got that under control, just in time for our E-commerce department to be formed, creating its own demands for space and logistics support.

Into all of this came Pokémon.

Due to the collectible nature of TCGs, every set – even a new base set – has a release date, both to drive excitement and to cut down on stores trying to poach each other’s customers by selling early. With the volumes involved in Magic and Pokémon, Wizards would have a surge of product through the warehouse with each release. And cards, like any cardboard, are susceptible to damage from excess heat & humidity. And our warehouse was in Texas.

During the summer of 1999, I recall a time when we had not only rented additional space in multiple other buildings near our warehouse, but also had 17 refrigerated semi trailers plugged in around the building, and at our various loading docks, just to hold all of the Pokémon as we got the bulk shipments prepared for a release.

A number of misprinted Pokémon cards entered circulation throughout the years, with some of them receiving corrections in later reprints. What kind of impact, if any, did these error cards have on the production side of things?

Carol:

Honestly, I don’t remember hearing anything about those, but I was only there for the first full year that we sold Pokémon. Errors certainly do happen: in Magic, we had the “Arabian Mountain”, a sole basic land card accidentally left in the common card print sheet after it was decided not to include any basic land cards. And we occasionally got bizarrely miscut cards, or cards from other games slipped in, due to really infrequent errors at a factory. Everyone does the best they can, and we fixed what we could, when we could.

I only recently found out about the “shadowless” Pokémon run: the first printing of what was supposed to be the unlimited base set. That wound up being a stealth limited edition instead, because the cards were missing the drop-shadows around the art frames (and they got Charizard’s wing color wrong on the display box), so Wizards simply updated the files at the printer as soon as they were able, and kept going, without changing the product code number or anything else. No one has official numbers on how big that “uncorrected” print-run wound up being.

The company had already seen tremendous growth prior to Pokémon, mostly thanks to Magic: The Gathering, but just how financially successful was Pokémon for WotC?

Carol:

To the best of my knowledge, during 1999, Pokémon generated far more revenue than Magic did, by multiples. And Magic was not slowing down either. Between the growth of Magic and the introduction of Pokémon, I believe that Wizards’ US revenues quadrupled from 1998 to 1999. I can only imagine what happened from 2000 onward.

On September 30th, 1999, WotC was sold to Hasbro. What was the mood at the company like in the months leading up to and following its sale?

Carol:

Side-note: Cathleen Adkison and I had a meeting in early 1994 with Hasbro Europe at the Nuremberg Toy Fair, where we told them that Wizards was for sale, and the estimated purchase price would be $5 million. I feel like this is important context for what eventually happened.

The mood at Wizards was a mixed bag. It was mostly positive for those of us who had stock, or at least stock options, though initially we weren’t sure whether this would be a cash deal, or a stock-for-stock one. For people who had invested back in 1993, it had been a long wait for liquidity. For more junior folks, or more recent hires, I’ve heard that the anticipation was more like dread, since everyone could see that it would mean big changes, and they weren’t going to see an extra dime.

I was senior enough that I got some visibility into the deal and had to work on some of the preparations. Specifically, the sale had been announced as a $325 million deal, but it included an adjustment for the company’s final asset valuation on the date the sale would close, September 30th, 1999 – at the end of our fiscal 3rd quarter. This meant a full-court press to raise the asset value as much as possible by that date, including bringing in and shipping out as much Pokémon as logistically possible. A box of booster packs in our inventory would simply be worth what we paid to print it (a wash), while a box of booster packs sold to a distributor or chain store would be worth its wholesale price, even if they hadn’t paid yet (a value many times the printing cost).

Converting cash into products, and products into accounts receivable, as quickly as possible was our entire focus in the Production/Logistics area that quarter. Sales offered customers some extended terms (60 or 90 days to pay, rather than the usual 30), in order to encourage them to buy all of the product they’d need for Christmas prior to September 30th. We turned everything around as fast as possible at the warehouse, and on the night of September 30th, when I was there helping supervise our end-of-quarter inventory counts, we had pallets out on the warehouse dock with shipping tickets slapped on them, marking them as “sold” and out of inventory, though they hadn’t physically left the building yet. I’ve heard that this sort of thing might have been made illegal later under Sarbanes-Oxley, but fortunately that wasn’t the law yet.

The upshot of it all was that our assets on the sale date were north of the original estimate by a full $50 million, bringing the initial sale price up to ~$375 million. On a side note, all Wizards shareholders were also promised 5 years of additional payments, tied to the extent to which sales of Magic: The Gathering topped $250 million/year (Hasbro anticipated that Magic would wane). And, in the one win for the ordinary Wizards employee, the deal included one last profit-sharing bonus for all of 1999. Our bonuses had varied over the years, but the scheme in place by then was that 10% of after-tax profits would be distributed to employees as a percentage of their total payroll for the year. It was called the “Christmas bonus”, but it was only calculated after the books were closed for the year, and distributed partway through the first quarter.

At the end of February 2000, five months after Hasbro purchased WotC, you left the company. What were your last few months of employment like?

Carol:

I was deep in internal company operations for my last few years at Wizards and my primary responsibility prior to the announcement of the sale had been creating process documentation and participating in an ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning, large-scale company software package) selection process. The first hint I heard of the sale was when we were stopped in our tracks, just on the point of signing up with JD Edwards. We had carefully assessed all of the major vendors, and – notably – determined that SAP (an ERP system) would be a very bad fit for Wizards, due to our constantly evolving business model.

After the sale went through, it was announced that Wizards would be implementing… SAP.

I went out to Hasbro HQ in Pawtucket [Rhode Island] several times for ERP implementation planning meetings, and at the first one we were shown around to several of Hasbro’s subsidiaries and had their overnight-rollup reporting process explained. I pointed out to a Hasbro executive that, if they were simply polling at night for a report, a subsidiary could be using any ERP – all major packages were able to supply custom electronic reports – and I was told that they had “69 million reasons we were going to be using SAP”, by which I understood that they’d already burned through that many dollars on their own implementation, which wasn’t even completed. The budget we had been planning for JD Edwards had been less than $20 million, so this immediately rang alarm bells for me.

In the end, two things convinced me that I truly needed to make an exit sooner rather than later.

First, on one of the ERP team’s visits to Pawtucket, our COO, Vince Caluori, opined that anyone working on the SAP project would really need to make a two-year commitment, and possibly even need to sign onto a contract for that. It would be too disruptive to have key people cycling in and out of a major undertaking like this. I’d seen how differently Hasbro managed their business than Wizards – they were old-school, rigid and hierarchical - and I wasn’t sure I wanted to sign up for an entire two-year stint of dealing with that.

Secondly, I participated in a meeting with Hasbro folks along with the consultants from IBM who were working on the Hasbro home-office implementation. I’d been in charge of Wizards’ product-numbering scheme for a couple of years at that point, so I wanted to make sure I understood how Hasbro were setting theirs up in SAP, assuming they’d force us to follow suit. They’d chosen to use a very rigid system based on UPC (Universal Product Codes) codes. I asked them how many new sellable products they created each year, and how many associated components, and did a bit of scratch math. I then politely asked if that would mean that they’d run out of numbering in less than 2 years. They looked to the IBM guys, who looked a little embarrassed and said I was right. Knowing that making any late-stage implementation change tended to add another million dollars to the tab, and that I was always going to be “that person”, pointing out any problems I saw, I figured I should leave them to it. They weren’t going to like me very much, and I’d find it all very frustrating.

Back in Renton [Washington] in early 2000, we got the good news that the final WotC-style profit-sharing “Christmas bonus” was going to come out to about 2/3 of our 1999 total pay, and it would be disbursed in mid-February. I talked to my boss, the VP of Logistics, and told him that – since I wasn’t able to make the long-term ERP commitment – I figured I should say a fond farewell, and asked how much notice he’d need. He said two weeks, so that’s what he got. I knew that, between everything, I could definitely afford to take a year off work, and that’s what I planned to do. I made sure one of my direct reports was completely up to speed on the whole ERP business and recommended that she be assigned to it, knowing that getting onto that project could be a good path to promotion for her.

When it got down to my last day, I got a surprise going-away party with colleagues from all over the organization, including Peter Adkison and the head of HR. We had nachos and margaritas (which I do not believe were virgin) and I got some funny gifts to send me off to “retirement” – a pair of fuzzy slippers, a copy of Soap Opera Digest – along with a very fancy sombrero and a hand-painted Mexican piggy bank (to hold all my riches!) sent up by the folks in the Texas warehouse.

That afternoon, I wound up talking to my friend Warren Wyman, an ex-FBI guy who was our head of security. He offered to help me with the couple of boxes I was taking from my office, and we had to stop for a good laugh over how I was being “escorted out by Security”. I happened to look across the parking lot as we went out and saw my old executive assistant from my time in Sales. He was also heading out with a box of his office stuff, and we weren’t the only two to finish up that day. The buyout had already triggered a lot of folks to leave, and the bonus was the cherry on top. The joke at the office was that we were all “calling in rich”.

How did the sale of WotC affect the Pokémon TCG?

Carol:

At first, everything ran along just as before. And even at the time I left the company, Hasbro had yet to make any major changes to Wizards’ internal operations. I later heard that I got out just in time, because Hasbro quickly started folding Wizards’ warehousing and logistics into their own, and the division I’d been in was slimmed down drastically.

Beyond that time, I only have rumor and supposition. I’ve heard it said that the licensors (Nintendo, Game Freak and Creatures) weren’t completely satisfied with Hasbro’s handling of the license. I’ve also heard that, once they established the Pokémon Company in Japan in 2001, they saw that it would be practical to handle the US market themselves, under a subsidiary. That would give them much better control of the IP, as well as more profitability – enough reason not to renew the license.

My impression is that Hasbro’s main motivator in buying Wizards was getting the Pokémon license, which they simply weren’t able to hold onto. In which there is some irony, because – even without Pokémon – Wizards has turned out to be the strongest part of Hasbro’s business.

What were some of your proudest moments while working at Wizards?

Carol:

I take the most pride in how I helped foster communication and collaboration between groups of people who – especially in the turmoil of our lightning-fast growth – could easily get siloed and work at cross purposes. I had a reputation as someone who “knew everyone”. I’d been there since the beginning, and [I] made a point of eating lunch with folks from all over the company and dropping in to catch up with department heads I otherwise wouldn’t see much. I cannot count the number of times people dropped into my office because they were trying to accomplish something and didn’t know who to approach about getting buy-in, or how to get folks on board so their project could succeed. I was always able to help make some connections, steering them to the knowledgeable folks and decision-makers they’d need.

I also strongly championed the inclusion of folks from multiple departments on our product teams. Getting direct involvement from a variety of perspectives made it more likely we’d get final products that could be effectively produced, marketed and sold. It also meant that more employees got insight into the whole process from initial design through production and onward, making them feel more invested in the success of those products and in the success of the company as a whole. And there was great value in simply bringing together folks who otherwise might not have gotten to know each other. It boosted morale and company cohesion, especially during all the tumult when reporting structures were changing so often.

My funniest proud story involves getting the best of Toys ‘R Us, back in 1994, but that’s really just about Magic: The Gathering, and it would take up an entire essay on its own. ;)

Where did your career take you after you left WotC?

Carol:

Back in 1995, my husband had volunteered for the big pre-Christmas layoff from Wizards. He did a stint as a house-husband, but quickly got bored and started designing board and card games. In 1996, he launched his own company, Cheapass Games, with Kill Doctor Lucky – a game that is still sold today. It was the first in a whole line of games that came in white envelopes, and later simple folded boxes, that did not include any dice, pawns or play money, since people could scrounge those for themselves.

I stayed out of the business while I was at Wizards, and for some time afterwards, but after taking some of the hiatus I’d promised myself, I found that Cheapass Games was in serious need of someone to handle the finances. So I took that on, along with ferrying boxes of inventory back and forth to the office and post office. Around that time, I had my daughter, too, keeping me pretty busy.

In 2006, James started working as a video game designer, so Cheapass Games went into hibernation, and I had a few years of being a grade-school mom. That’s when I started noticing Pokémon again. We even tried bribing our daughter to do chores with some old Pokémon booster packs I had, but fortunately she wasn’t interested (considering what they were worth later, those would have been expensive chores!). I also started helping my long-time friends Phil and Kaja Foglio with their Girl Genius business.

In 2011, James went through a layoff, and I took the opportunity to work as Director of Strategy at a software non-profit, where I spearheaded getting funding for a major project. And just as that project wrapped up, James started reviving Cheapass Games with deluxe editions through Kickstarter, and the Foglios quickly followed suit for their graphic novels. I wound up splitting my time for a number of years between the two publishing businesses, concentrating on the operational side of crowdfunding campaigns: budgeting, printing and production, warehousing and fulfilment.

Eventually, Cheapass Games grew to the point where I needed to work there full-time, and in 2016, we incorporated, just in time for our largest crowdfunding project ever: “Tak: A Beautiful Game” with author Patrick Rothfuss, which raised $1.4 million from 11,000 backers.

By 2019, I could see that the hobby game market was changing, and more importantly, consolidating. We got an opportunity to license the Cheapass Games product line to a larger company, and [we] took the chance. The next year, when the pandemic hit, it turned out to be a boom time for Pokémon collecting, but a really rough time for a lot of smaller game companies. I felt that we’d dodged a bullet.

Then as the pandemic retreated, I took up another outside job, as Director of Operations for a video game startup. I’m always a glutton for risk, I guess! Unfortunately, that company failed, mostly due to a lack of funding - as so many startups do. I have been doing some consulting since, with stints for companies like Ravensburger (Lorcana) and Slugfest Games (The Red Dragon Inn). I’m currently back applying for corporate jobs. So, if anyone has a small to mid-size company that needs a Chief of Staff, COO or VP of Operations, or just needs some consulting, hit me up!

Pokémon products have always been a highly collectable product, and as you mentioned, the interest in Pokémon cards, especially those printed by WotC, went through the roof around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, causing their value to skyrocket. What are your thoughts on that?

Carol:

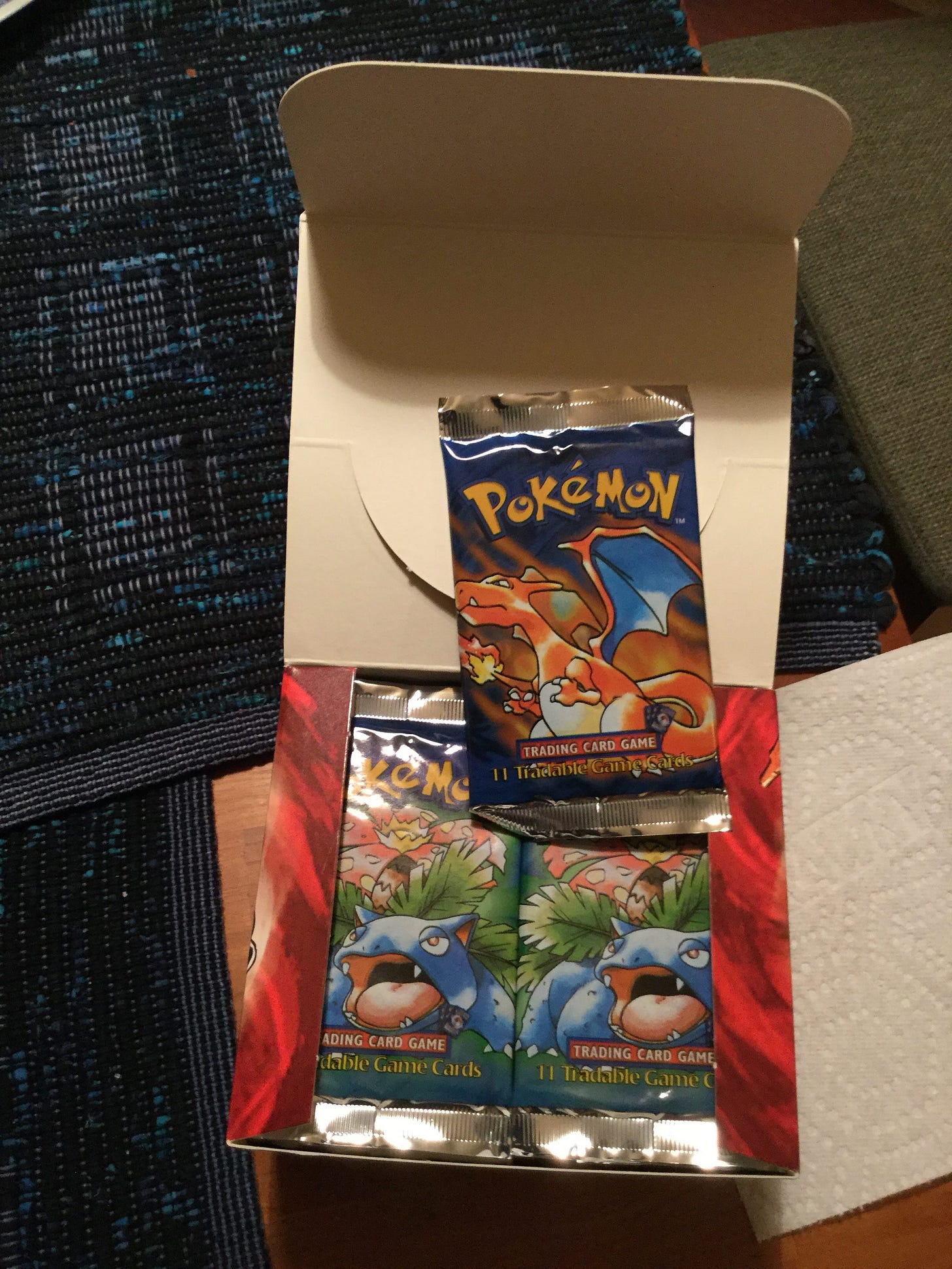

Many, many of my old work friends from Wizards have worked at The Pokémon Company International over the years, so they were always more in touch with what was going on with Pokémon than I was. One of them reached out to me in 2021 to let me know that there had been a resurgence of interest in the original Wizards Pokémon sets. He asked if I wanted to sell any of my old boxes and then helped me make contact with an influencer who could assist.

I had only held onto my Pokémon cards because – many years before – I’d gone to sell my Magic cards, which were already fetching very healthy prices, and I’d been offered $25 each for full boxes of WotC Pokémon, which was less than their original wholesale value! No thank you, I said, and [I] tucked them away to wait.

The value of collectibles is always unsure, and I’ve seen so many ebbs and flows over the years. When 2021 rolled around, I was definitely happy to cash in my old Pokémon, and very happy to see the cards going to people who were genuinely thrilled to get them. They weren’t doing anyone any good sitting on a shelf in my closet.

That spot now holds a few Lorcana cards. Just in case.

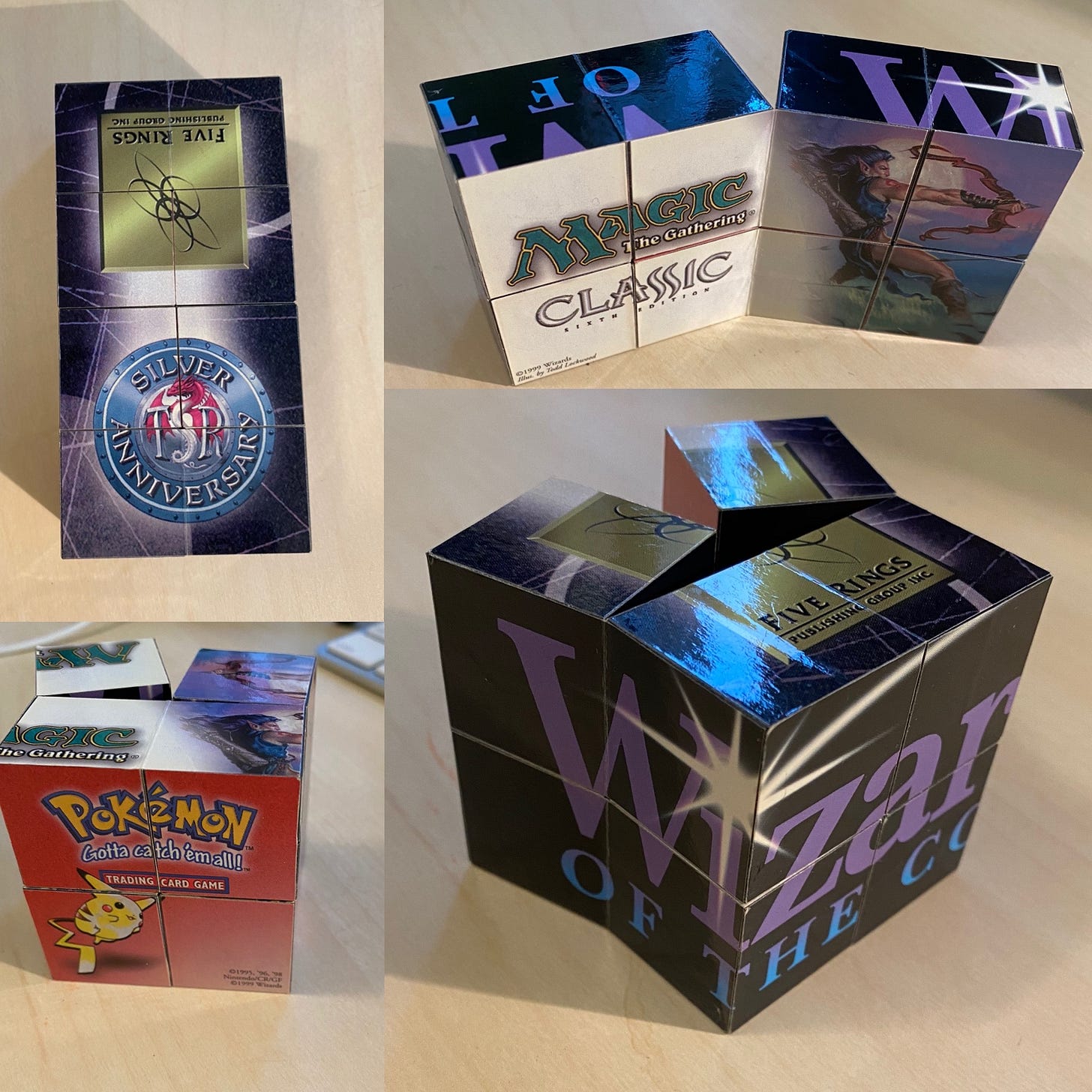

Are there any Pokémon products you were able to keep from your time at the company?

Carol:

I have let all of my Pokémon card boxes and booster packs go at this stage. I still have one odd little marketing knickknack with the Pokémon logo on it, along with a stuffed Charizard and a poster of Pikachu at the beach that I bought at a Japanese import store and kept in my office at Wizards. So, just mementos.

I still wear my old WotC jean jacket with the Hurloon Minotaur on the back, and I have a few Magic cards still, including a small stack of original Rubinia Soulsingers, because I modeled for that one.

It has been almost twenty-five years since you left WotC. Looking back, what are your fondest memories of working at the company?

Carol:

For me, it will always be about the people I got to work with. Going through the raging fires of a startup together creates some lasting bonds – you get to know who has your back, and who you’d take an arrow for. I could go on for hours about all the business trips and adventures we had, from coffee and beignets at Café du Monde [in New Orleans] at four in the morning, to driving down the autobahn in a blizzard, to drinking beers at Ranger Stadium [Ft Worth]*. It was a wild ride, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

* The manager of our warehouse in Grand Prairie, TX took me out to a ballgame one summer evening. I have no idea who was playing (beyond the Rangers), since we really went to drink beers. ;)

Carol, I am incredibly thankful for your time and for sharing your memories and stories about your time working at Wizards of the Coast. Before we wrap this up, do you have any final comments you would like to make?

Carol:

I think I’ll just say that I have been incredibly lucky, and I don’t take that for granted. I’ve gotten to work with so many great people and on such great games over the years – more than I ever dreamed of. And I’m not done yet!

I want to thank Carol for taking the time to answer my questions, and for sharing a rare insight into her time working at Wizards of the Coast. I wish her all the very best of luck with her future.

That’s it for another week of Johto Times! As always, thank you for subscribing and taking the time to read what I publish each week. If you enjoy what Johto Times provides, be sure to share our newsletter with your friends and loved ones to help us reach even more Pokémon fans. For Discord users, you’re welcome to join our server for the latest notifications from our project. We are still open to sharing your mailbag entries, so if you have anything you would like to share with us, drop us a line by visiting this link to contact us directly!